Virtual Reality’s Flaw: Exploiting Human Emotions

The use of virtual reality (VR) to record human suffering and promote donations brings into question the line between humanity and technology. The ambiguity and complexity linked with this form of media calls for an analysis of current VR practices, its emotional implications, and potential steps for the future. How is our capacity to feel emotion linked with our humanity? Are our emotions degraded when they are stimulated by a machine? Abe Streep attempts to answer these questions in his article “One Startup’s Quest to Save Refugees with Virtual Reality”. He outlines some of the advantages and disadvantages of using VR for increased social awareness by citing the work of Ryot, an immersive media company focused on humanitarian aid. Ryot believes that VR will be “the future of news”. But if VR were to be the main form of media, what would the social and emotional impact be on humanity? The ambiguity of the impacts of VR into mainstream media makes it difficult to definitively point out the social benefits or lack thereof. Overall, the current optimistic view of VR shared by Ryot on VR’s potential role in helping refugees must be taken with a grain of salt. While VR has the potential power to change lives through monetary support, current practices abuse VR and strip our humanity in the process.

Companies such as Ryot that use VR as a way to obtain monetary funds are abusing the capacity of VR to generate income. While the money is used for aid and relief efforts, it makes a difference whether the donations are motivated by a true desire to help or, as Streep writes, “virtually induced guilt.” Is it truly fair to take guilt money, especially for humanitarian causes? Moreover, VR is said to be a way to transport people to a different place, a different time, under different circumstances. In certain situations, this may be a great way to gain a closer understanding of living conditions completely different than one’s own. It allows humans to mimic the effect of standing in somebody else’s shoes. Yet the goal for companies like Ryot is not to “hide behind neutrality” or let the audience decide for themselves; ultimately, their goal is to get people to donate. VR is not expanding knowledge and cultural awareness but exploiting wealth. Companies such as Ryot use VR as a form of technology to instigate some sort of emotional response. But in the process of capitalizing on human emotions, our humanity is stripped. Humanity has become a capitalist venture, one that can be quickly taken advantage of as long as one doesn’t care about where the money comes from. Rather, current practices need to start moving towards making long lasting social effects through VR that can change opinions across the world.

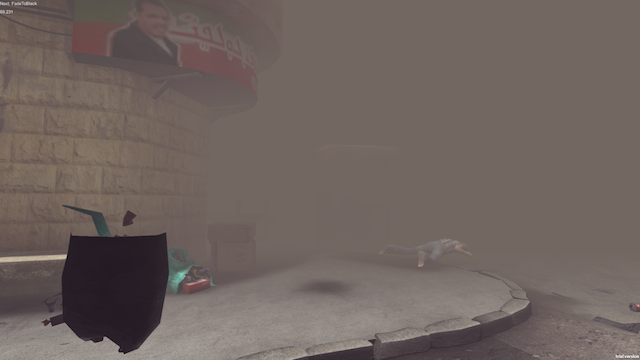

Image: YouTube video still / Malmo

Image: YouTube video still / Malmo

Images of Project Syria, a tool utilizing VR to bring the Syrian War to life. Image: YouTube video still / Malmo

Additionally, with the advent of warlike videogames, it is possible that dangerous situations shown could be seen as just another game. Maybe Americans have already distanced themselves too much from any reality outside their own. Streep mentions this when he writes that VR could enable “the privileged to traipse in and out of videogamelike crisis zones.” The current practices associated with VR create no distinction between being immersed in a video game versus in a severe social situation such as the Syrian refugee crisis. For example, Malmo writes about Project Syria, a project aimed to give people a more realistic experience by placing them in the crossfire of the Syrian war. However, look at the video and the photos (above) about the project: the animations and setting look exactly like current videogames. This abuses current technology and trends because it is creating a brand of “disaster tourism”; too much of a good thing is not good at all. In today’s day and age, the values of society have changed to emphasize what is fast and easy: visual media that can be quickly looked at. Companies like Ryot are overusing VR to to saturate the news. This negates the positive impact of incorporating lots of VR videos as humans soon will no longer be subject to the induced guilt caused by this new form of media. While VR is trying to gain a wider audience for refugees and the like, it is also playing right into mainstream media rules, even enhancing them and pushing our society more overboard.

VR is also misused, or at least misunderstood, because of how the director captures the subject of the videos. Streep claims that VR creates subjectivity in media by moving towards greater human empathy by disregarding current media standards for objectivity. In order to do so, the filmmakers need to use poignant moments. However, a UN panelist said that with VR, “the opportunity to give a voice to refugees is unprecedented.” These two statement are contradictory. How can VR give a voice through a subjective point of view? By picking footage certain footage and placing the camera in specific locations, the producer is limiting the voice of the subject to what the producer has decided will be most beneficial. In Clouds Over Sidra, a VR film about a Syrian refugee, creators Gabo Arora and Chris Milk have created a narrative about her life to show the differences between our lives and hers. Each clip from a film serves one purpose: to create greater empathy. And that limits the audience’s view of the subject. Skeptics may argue that VR still provides knowledge of people around the globe that would be otherwise unseen. Yet, without acquiring the objectivity that VR sets to obtain, there is little difference between this form of media and regular film used to convey other situations. The idea of no frames is perfect as nothing is left behind, but one still has to consider the limitations associated with technology and people.

A visual disconnect is seen in this photo as David Darg takes a video with a VR camera while refugees arrive at Lesbos, Greece. Guy Martin / Panos.

Chris Milk, the founder of Vrse, said that “ultimately we become more human” with VR. Milk argues that VR brings us closer to who we are. Yet isn’t it ironic that technology is supposedly creating relationships after years of people complaining that technology is tearing society apart by creating a screen barrier? VR is an even greater physical barrier, completely encompassing somebody into a virtual world. Humanity is shifting towards global connections and away from the intimate personal connections that come with physical contact. VR is picking one at the expense of the other. Human reliance on technology for any type of connection is becoming more and more invasive. Subjects are relying on these forms of media for monetary support, and humanity is being confined by the parameters set by VR. Moreover, when news articles or VR films are taken lightly, it strips away the human dignity of the subjects. VR is exhausting the number of things that humans have a strong emotional connection to. This fleeting trend is linked with the capitalization of human emotion. For instance, the image pictured shows a man taking a view with a VR camera of refugees arriving on land. But why didn’t the videographer just help the people off the boat? The visual detachment between the boat and the lone figure calls into question VR and its role in journalism. VR and media emphasize the creation of relationships across seas instead of face-to-face relationships.

Einstein said that “It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity.” However, with the right tools and techniques, it is possible for VR to rise above the current exploitations and disadvantages to promote social awareness in a humanitarian way. The continued exploration of what it means to be human emotionally will be extremely important as the future impinges on the present and the differences between human emotions and machine rigidity decrease. Filmmakers should look into the potential of other techniques of embodiment to create fully sensual experiences. The problem is not that VR has no frame, but that society is still stuck in the idea of no frames. But, there is more to media than just imagery. Streep ends his article by writing “I turn my head in all directions, listen to the virtual wind, and recall the most haunting element of that place: the smell.” Streep implies the importance of sensual experience that VR has not yet figured out how to convey. Touch and smell are not aspects that can be replaced, at least not yet.

Works Cited

Carr, David. “Unease for What Microsoft’s HoloLens Will Mean for Our Screen-Obsessed Lives.” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 25 Jan. 2015. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

Clouds Over Sidra. Dir. Gabo Arora and Chris Milk. Perf. Sidra. WITHIN. Within Unlimited, 2015. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

Malmo, Christopher. “A New Virtual Reality Tool Brings the Daily Trauma of the Syrian War to Life.” Motherboard. VICE Media LLC, 23 Aug. 2014. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

Project Syria Demo. Dir. USC School of Cinematic Arts. YouTube. YouTube, 31 Jan. 2014. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

“RYOT: About.” RYOT. RYOT. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

Streep, Abe. “One Startup’s Quest to Save Refugees With Virtual Reality.” Wired. Conde Nast, 15 July 2016. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.

Watercutter, Angela. “VR Films Work Great for Charity. What About Changing Minds?” Wired. Conde Nast, 01 Mar. 2016. Web. 12 Feb. 2017.